A long-run view on monetary policy - Part 5: How well does the SNB's mandate fit?

This is Part 5 of a series of articles on Swiss monetary policy I wrote jointly with Simon Schmid for Republik. They kindly agreed that I can publish an english version on my blog. Enjoy:

In many respects, Switzerland is a special case. The SNB's mandate is no exception. The SNB is one of the only central banks that aims for an inflation rate between 0-2%. In practice, this means that the inflation rate was below 1% on average since 2000. Most central bank's inflation targets amount to 2% or higher. The last article of this series deals with the challenges that this low inflation target raises for Swiss monetary policy.

In many respects, Switzerland is a special case. The SNB's mandate is no exception. The SNB is one of the only central banks that aims for an inflation rate between 0-2%. In practice, this means that the inflation rate was below 1% on average since 2000. Most central bank's inflation targets amount to 2% or higher. The last article of this series deals with the challenges that this low inflation target raises for Swiss monetary policy.

The limited scope for interest rate cuts

To start, we have a look at short-term interest rates; these are interest rates for three-month interbank loans. The SNB uses such an interest rate to communicate its policy stance. The following chart shows how interest rates developed since the financial crisis in nine countries and monetary unions. We show the difference between the maximum attained before the crisis and the minimum after the crisis. This shows how much scope the corresponding central bank had to ease policy with conventional interest rate cuts.

Figure 1: Limited scope for interest rate cuts in Switzerland

|

| Source: OECD. The green bars show the maximum level of short-term interest rates just before the financial crisis. The blue bars the minimum level of interest rates in the years after the financial crisis. The red bars show the difference. A lager difference implies that there was a larger scope for cutting short-term interest rates during the crisis. |

We see that short-term rates declined in all countries. The largest difference (the largest red bar) we observe for New Zealand (7 percentage points). In Switzerland, however, interest rates declined only by 3.9 percentage points, even though the SNB introduced negative interest rates.

We already discussed in an earlier article, that the low interest rates are at least partly a consequence of low inflation. In addition, interest rates cannot fall (much) below zero as long as there is currency that earns zero interest. As a consequence, a country with a low inflation target has less scope for interest rate cuts in a crisis and it has to resort to non-conventional policy actions.

Interest rates and appreciation pressure

There are two main reasons why interest rates in Switzerland are lower than abroad: the lower inflation target and a so-called "interest rate bonus" that is usually attributed to the stable economic environment. This means that, in a crisis, interest rates abroad fall more strongly than in Switzerland. And, because interest rates cannot fall much below zero, the difference between Swiss interest rates and interest rates abroad becomes smaller.

To understand why this is particularly relevant, recall that Switzerland has experienced strong appreciation pressure during the financial crisis. This is also related to the narrowing interest rate differential: investors find it relatively more attractive to invest in Switzerland because the yield on foreign investments falls more strongly than the yield on Swiss investments. As a consequence the Swiss franc appreciates.

The Swiss National Bank can then either stand by and watch as the Swiss franc gets stronger and may even cause a recession and deflation. Or, it can counter these adverse dynamics actively and expand its money supply and absorb the higher demand for Swiss francs. The latter means that the SNB buys foreign currency and expands its balance sheet.

The crucial point is, however, that the appreciation is not merely caused by exogenous foreign factors but can be partly traced back to the SNB's monetary strategy and mandate. The low inflation target reduces the scope for interest rate cuts and therefore amplifies appreciation pressures in crises.

The crucial point is, however, that the appreciation is not merely caused by exogenous foreign factors but can be partly traced back to the SNB's monetary strategy and mandate. The low inflation target reduces the scope for interest rate cuts and therefore amplifies appreciation pressures in crises.

Small interest rate cuts and large balance sheet expansions

In other words, there is a connection between the Swiss definition of price stability and the large foreign exchange interventions by the SNB. We can visualize this relationship by looking at cross-country data. The following figure shows how much each country cut its short-term interest rate on the horizontal axis (this is the same statistic as in the previous figure). On the vertical axis, we display the growth in the monetary aggregate M1 from 2007 to 2016.

|

| Source: OECD. The difference in interest rates is calculated as in the chart above. Growth in M1 is calculated over the period from 2007-2016. |

We see that Switzerland had little scope to cut interest rates and expanded the money supply most strongly. In the UK, for example, the potential to cut short-term rates was larger and the monetary aggregates grew less strongly.

Importantly, this analysis is not about the effectiveness of monetary policy; recall that we showed in a previous article that Switzerland fared relatively well in terms of real economic growth and stable prices during the crisis. But, the question is one of efficiency: how much does the central bank have to expand its balance sheet and the money stock to fulfill its mandate? In Switzerland, this question is also related to the introduction of negative interest rates. In 2015, the SNB lowered its interest rate target to -0.75%, which was partly heavily criticized.

If we think that a large balance sheet and negative interest rates do not pose serious problems, we may argue that efficiency does not matter. We can also ask, however, whether there are alternatives to loosen monetary policy without resorting to large balance sheet expansions or negative interest rates.

Importantly, this analysis is not about the effectiveness of monetary policy; recall that we showed in a previous article that Switzerland fared relatively well in terms of real economic growth and stable prices during the crisis. But, the question is one of efficiency: how much does the central bank have to expand its balance sheet and the money stock to fulfill its mandate? In Switzerland, this question is also related to the introduction of negative interest rates. In 2015, the SNB lowered its interest rate target to -0.75%, which was partly heavily criticized.

If we think that a large balance sheet and negative interest rates do not pose serious problems, we may argue that efficiency does not matter. We can also ask, however, whether there are alternatives to loosen monetary policy without resorting to large balance sheet expansions or negative interest rates.

It depends: on credibility

So, are there more efficient alternatives? It depends - on whether the announced measures are credible. To understand this we have to distinguish between to different kinds of non-conventional policy measures.

The first kind, uses changes in the composition or size of the balance sheet to affect financial markets. The main idea is that financial markets are inefficient (or subject to substantial transaction costs) and the central bank can correct distortions through direct interventions in particular markets (for example in the mortgage market or in the foreign exchange market).

The second kind, affects expectations of market participants about future monetary policy. A central bank can, for example, promise to defend a foreign exchange peg in order to increase future inflation. Or, it can promise to keep future interest rates lower and accept a somewhat higher inflation rate (forward guidance). Such announcements imply a more expansionary monetary policy stance.

If the public (in particular financial markets) believe such a promise, they expect lower future interest rates and higher future inflation. The trick is that this immediately lowers long-term real interest rates because investors immediately shift their portfolios to benefit from the lower future interest rates. This means that the cost of borrowing declines and the currency immediately depreciates.

Put differently, the main difference compared to balance sheet expansions is that, if the promises are credible, the central bank does not have to intervene; market participants conduct the transactions for the central bank. The second kind of interventions is therefore more efficient because the central bank has to expand its balance sheet less to obtain the same result. If the announcement is not credible, however, the central bank has to move from words to deeds and intervene in financial markets.

Credibility in four examples

We can illustrate this fact by four examples:

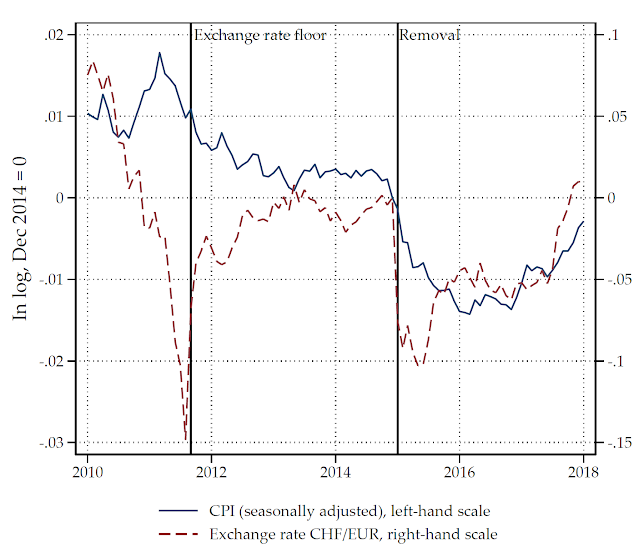

In Switzerland, the Swiss National Bank announced a minimum exchange rate vis-à-vis the euro in 2011. If necessary, it announced, it would intervene in foreign exchange markets without limit. At the beginning, this announcement was credible and the SNB did not intervene much. Over time, however, the announcement lost its credibility. The reason is that Switzerland has a lower inflation target than the euro area. As a consequence, the Swiss franc has to appreciate on average and over long time periods by 1% each year. A minimum exchange rate against the euro was therefore not compatible with the different mandates of the two monetary areas. Despite large interventions, the minimum exchange rate was abandoned in early 2015.

In Denmark, however, the Danish National Bank successfully defended an exchange rate peg during the same period. However, the Danish National Bank introduced a fixed exchange rate already in 1982 and officially communicates that it adopts the inflation target set by the ECB.

In the Czech Republic, the central bank also introduced a temporary and symmetric exchange rate target in 2013. Although the Czech National Bank also had to intervene heavily in foreign exchange markets, it has roughly the same inflation target as the ECB. By now, we have seen that the policy was successful and the Czech National Bank abolished the exchange rate target with much less turbulence than the SNB.

In 1978, the SNB already introduced a minimum exchange rate; but, vis-à-vis the Deutschmark. At the time, the Bundesbank had a similar inflation aversion as the SNB and the average inflation rate in both countries was practically identical. A fixed exchange rate was therefore more in line with the SNB's mandate and therefore more credible over the long term.

Conclusion

Since the financial crisis, the SNB engaged in massive non-conventional policy actions and an unprecedented balance sheet expansion. We have seen that this can be partly traced back to the low-interest rate environment, the loss of traction during the financial crisis, and the SNB's own mandate with a particularly low definition of price stability.

Does it make sense to increase the SNB's inflation target? Of course, there are many more alternatives that we have not had the time to discuss yet. And, of course, there are pro's and con's. On the one hand, the low inflation target led to a period with historically low and stable inflation. On the other hand, the low inflation target exacerbates the asymmetric response of the SNB in recessions and therefore amplifies safe haven appreciations. Because interest rates cannot fall much below zero, it is much more complicated for the SNB to fight deflationary pressures than to counteract inflationary pressures. The large balance sheet compared to other industrialized countries is partly a result of this asymmetry.

Two years ago, the Federal Council published a report on Swiss monetary policy. The report argues that the monetary strategy of the SNB worked well during the crisis. According to the report, the SNB has at its disposal all necessary tools to fulfill its mandate, namely, ensure price stability and take into account the business cycle.

True, the SNB can fulfill its mandate and largely has. The necessary means, however, were staggering. Against this backdrop, we should think about alternatives and whether the SNB should have more scope to cut interest rates when the next crisis hits.

Comments

Post a Comment