A long-run view on monetary policy - Part 1: Are central banks devaluing our currency?

This is Part I of a series of articles on Swiss monetary policy I wrote jointly with Simon Schmid for Republik. They kindly agreed that I can publish an english version on my blog. Enjoy:

Since the financial crisis started 10 years ago, interest rates hit record lows, unemployment first rose and then gradually fell, and central bank's balance sheets ballooned to unprecedented levels. Do we have to fear runaway inflation? Or were the unprecedented policies of central banks just the normal response to an exceptional crisis?

In the coming weeks, we will answer these and more questions in a series of posts. We provide an assessment of Swiss monetary policy without resorting to unsubstantiated claims and simple solutions. We would like to explain the concepts and issues based on historical statistics and differenciated analyses. The goal is to provide an in-depth, but, generally accessible assessment of what happened with Swiss monetary policy since the financial crisis and beyond.

Since the financial crisis started 10 years ago, interest rates hit record lows, unemployment first rose and then gradually fell, and central bank's balance sheets ballooned to unprecedented levels. Do we have to fear runaway inflation? Or were the unprecedented policies of central banks just the normal response to an exceptional crisis?

In the coming weeks, we will answer these and more questions in a series of posts. We provide an assessment of Swiss monetary policy without resorting to unsubstantiated claims and simple solutions. We would like to explain the concepts and issues based on historical statistics and differenciated analyses. The goal is to provide an in-depth, but, generally accessible assessment of what happened with Swiss monetary policy since the financial crisis and beyond.

The startling history of inflation

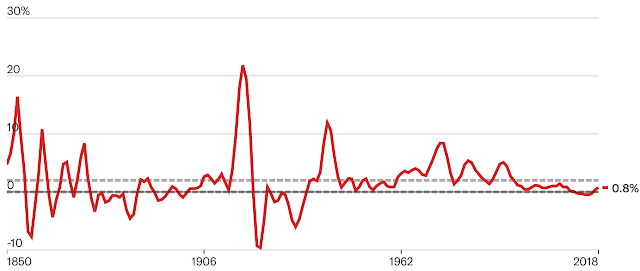

The first part of the series deals with a mystery that occupies central bankers on a daily basis: Inflation. We start with a chart showing the long-run evolution of the change in the average price of consumption goods in Switzerland over the past 167 years. The chart shows percentage changes over a year, but, averaged over three years to smooth temporary fluctuations that most central banks actually don't really care about. We also show two lines at 0% and 2% representing the range in which the Swiss National Bank would like to stabilise inflation nowadays.

Figure 1: The time of large inflation swings is over

|

| Inflation of Swiss consumer prices and today's definition of price stability (0-2%). Prices for individual goods and services rise and fall all the time. If we observe price increases for many goods at the same time, we call this inflation. Inflation reduces the purchasing power of money because we can buy less goods and services for, for example, a 10 Franc bill. Inflation is usually measured as the percentage increase of a price index over a year, in Switzerland usually the Swiss consumer price index. Sources: Daniel Kaufmann (2018): «Nominal Stability over Two Centuries». Most recent values extended with forecasts by SECO. |

If we have a look at the chart starting today and going back in time, we note that over the last 20 years, inflation was unusually stable. The three-year average remained almost always between 0% and 2%.

Between 1960 and early 1990, inflation fluctuated much more strongly. In this period, the Bretton-Woods-System of fixed exchage rates collapsed and, afterwards, most central banks used monetary targets to calibrate their policies. We observe several bouts of inflation: prices of every-day goods such as bread and hair cuts rose at times by almost 10% a year.

After WWII, between 1945 and 1960, we have another period with relatively stable inflation. At the time the Bretton-Woods-System was already in place, however, countries used capital controls and were therefore able to conduct a relatively independent monetary policy despite fixed exchange rates. In addition, US monetary policy, which was at the center of the system and therefore played a special role, was still relatively stable at the time.

During the two World Wars, inflation clearly rose above 2%. Particularly during WWI monetary policy was subordinated to the war economy; the Swiss National Bank, even, considered itself a 'war bank'. Shortly after WWI and during the Great Depression of the 1930s there were sharp deflationary pressures, that is prices declined on average. Overall, inflation was substantially more volatile than what we are used to today.

Turning to the 19th century, we have to consider that the data quality is lower than for modern statistics - the figures are retrospective estimates so that comparisons over time have to be taken with a grain of salt. Still, we observe strongly fluctuating inflation rates between 1850 and the late 1980s, which are not in line with today's definition of price stability. Somewhat more stable inflation rates we observe from 1890-1914 during the last years of the Classical Gold Standard.

From a historical perspective we are therefore experiencing an unusual situation: Inflation is stable over quite a long time period. It is save to say that the Swiss National Bank does not devalue our currency. If anything, inflation was slightly too low since the financial crisis.

What is lacking so far, however, is a global perspective. This is particularly important for Switzerland as a small open economy. Indeed, Swiss inflation follows, at least at a first glance, inflation in other countries.

The next figure shows the inflation rates of the UK, US and Sweden, again, from 1850 onwards and averaged over three years. We observe strong comovements between the inflation rates of the three countries and Switzerland: The volatile inflation rates in the 19th century, the relatively stable inflation rates during the Classical Gold Standard, the Great Inflation of the 1970s and 80s, as well as the low and stable inflation rates starting in the 1990s.

What are the reasons for this comovement? Often we hear that global economic linkages in trade and finance are the main culprit. This cannot explain, however, why we obsereve a strong comovement over almost all periods. I find it more likely that it can be traced back to the way the monetary system was organized and that central banks adopted similar monetary strategies.

The next figure shows the inflation rates of the UK, US and Sweden, again, from 1850 onwards and averaged over three years. We observe strong comovements between the inflation rates of the three countries and Switzerland: The volatile inflation rates in the 19th century, the relatively stable inflation rates during the Classical Gold Standard, the Great Inflation of the 1970s and 80s, as well as the low and stable inflation rates starting in the 1990s.

Figure 2: Similar inflation developments in many countries

|

| Sources: Ryland Thomas and Nicholas Dimsdale (2017): «A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data»; Rodney Edvinsson and Johan Söderberg (2010): «The Evolution of Swedish Consumer Prices 1290–2008»; Lawrence H. Officer and Samuel H. Williamson: «The Annual Consumer Price Index for the United States, 1774–Present». Values for 2018 are updated with forecasts from the OECD. |

What are the reasons for this comovement? Often we hear that global economic linkages in trade and finance are the main culprit. This cannot explain, however, why we obsereve a strong comovement over almost all periods. I find it more likely that it can be traced back to the way the monetary system was organized and that central banks adopted similar monetary strategies.

- During the Classical Gold Standard, the interwar periods, and during the Bretton-Woods-System, monetary policy was integrated in global monetary systems. Under these arrangements, bilateral exchange rates were fixed. Therefore, inflationary or deflationary pressures spilled over to other countries and spread among the participants of these systems. These inflation fluctuations were triggered by changes in the price of gold (Classical Gold Standard) and US monetary policy (Bretton Woods).

- After the break-up of the Bretton-Woods-System in 1973, central banks had the possibility to conduct an independent monetary policy but actually lacked experience. Inflation rose quickly in many countries. After some experimenting central banks around the world improved their strategies and increasingly focused on price stability.

Accordingly, inflation is not merely a global phenomenon but depends crucially on national monetary policy. This is also reflected by the fact that there was a bout of inflation in the US during the Civil War after 1860, but also, a much higher inflation rate in the UK in the 1970s.

But how well does a central bank actually control inflation? We will come back to this question in Part IV of the series. Before, we have ask ourselves another important question when it comes to monetary policy.

Why is inflation harmful?

Unexpected rises or declines in the genral level of prices are harmful, because they hamper economic activities. Imagine, for example, Mrs Driver opens a screw factory using a loan from the bank of 2 million Swiss Francs. Of course, she has plans for the future: she would like to produce screws over the next 10 years, one million per year, at 20 centimes a piece. This would yield revenues of 200,000 Francs per year

- If Mrs Driver's expectations are correct, and she can sell the screws at 20 centimes a piece (price stability), she will make 2 million Francs of revenues in 10 years and can pay back the loan (without interest)

- If, however, all prices decline by 10% (deflation), her revenues will amount only to 1.8 million Francs and she cannot repay her loan.

- If prices increase by 10% (inflation) she can repay the loan without problem and makes an unexpected profit. The bank, however, receives less than expected (adjusted for inflation) and therefore makes a loss.

Such planning mistakes occur not only in a screw factory, but also, in tax policy, wage negotiations, and consumer decisions. With stable and predictable inflation rates, such planning mistakes can be avoided.

«Price stability (…) is an important condition for an efficient functioning of the market», we read in the Federal Council dispatch on the revision of the National Bank Act, «because prices steer the production and use of single goods in our market economy» (own translation).

Price stability does not mean, however, that all prices of goods and services remain unchnaged all the time. Quite the contrary. For prices of individual goods to fulfill their steering function they have to adjust constantly. How, then, should we measure price stability and the success or failure of monetary policy?

- Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan, two former presidents of the US central bank, proposed in the 1980s and 1990s an informal definition. Accordingly, price stability is achieved if market participants simply ignore unexpected changes in the general price level because they are so small.

Although most economists agree with this informal definition, we can hardly measure or assess whether the central bank in fact delivers on its mandate.

- Greenspan's sucessor Ben Bernanke therefore emphasized that we should use macroeconomic indicators, such as inflation or nominal GDP, to assess the stability of the monetary background of an economy. The SNB's new monetary policy strategy rests on a similar idea.

- The SNB equates price stability since the introduction of the new monetary policy strategy roughly 20 years ago with an annual increase in the consumer price index of 0% to 2%. Temporary and unpredictable deviations from this range are also acceptable.

- Like most central banks, the SNB has a positive target (range) because official price statistics overstate inflation somewhat.

And now we also know the common lesson central banks learned in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Many central banks introduced monetary policy strategies that focused on stabilizing domestic inflation rather than subordinating themeselves to fixed exchange rates. This strategy received the name Inflation Targeting and is closely related to the SNB's strategy. To understand the low and stable inflation rates during the past 20 years, we have to understand what Inflation Targeting is all about.

The power of expectations

Inflation Targeting is based on a key idea: market participants should adapt their personal inflation expectations to a level consistent with the inflation target set by the central bank or the government.

The result is similar as for a speed limit. If an official speed limit is introduced, most car drivers adapt their behavior and drive roughly in line with the limit. Of course, some drive faster and some drive slower. But, the official limit acts as an anchor. It makes sense to drive about as fast as the speed limit if an individual driver thinks the other participants comply as well. As a consequence, the speed limit makes traffic more fluid and safer. The speed limit is supported by the police. Those who drive too fast (and maybe too slowly) risk a fine.

The latent threat of a fine is crucial that the system works. The larger the fine is, the more likely drivers comply with the speed limit. As a consequence, the police has to conduct fewer traffic checks.

Inflation Targeting works similarly. If firms, consumers, and financial market participants believe that the central bank will defend the inflation target at all cost, the central bank has to intervene less to actually achieve it. This means, the central bank has to respond with smaller changes in interest rates if inflation temporarily rises or falls below the target.

The financial crisis was actually one of the first serious tests of modern policy regimes that focus strongly on stable inflation. And, at least when it comes to stabilising inflation and inflation expectations, it passed. The next illustrates this for the US. Since 2000, 10-year inflation expectations hovered around 2%. Despite wild swings in actual inflation just before and after the financial crisis, inflation expectations remained largely stable. Over the past 10 years some commentators argued that we will drift in a deflationary spiral; other feared that inflation will spiral out of control because of nonconventional policy measures. Neither happened.

The financial crisis was actually one of the first serious tests of modern policy regimes that focus strongly on stable inflation. And, at least when it comes to stabilising inflation and inflation expectations, it passed. The next illustrates this for the US. Since 2000, 10-year inflation expectations hovered around 2%. Despite wild swings in actual inflation just before and after the financial crisis, inflation expectations remained largely stable. Over the past 10 years some commentators argued that we will drift in a deflationary spiral; other feared that inflation will spiral out of control because of nonconventional policy measures. Neither happened.

Figure 3: An anchor in turbulent times

|

| We cannot directly measure inflation expectations. However, we can infer them from financial market data or ask professional forecasters and consumers in surveys. The chart shows the average US inflation rate expected over the next 10 years of professional forecasters (survey) and estimated using financial market data and economic theory (model). The blue line shows actual inflation. Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland; Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. |

To conclude, inflation remained remarkably low and stable during the past 20 years, not only in Switzerland but also in other advanced economies. If anything, inflation was not too high but actually tended to fall below the targets of the various central banks. But also, fears of persistent deflation have been ungrounded. The modern monetary policy strategies of the Inflation Targeting variety, and the policy actions taken by central banks to ensure that the price level does not decline despite a severe financial crisis, are likely two of the important reasons for the unusually stable inflation rates.

Of course, we have to be careful. We do not know for sure whether monetary policy is the main reason for the low inflation rates. Inflation may be low not because of good monetary policy but despite of bad monetary policy. Some commentators indeed argue that this is the case. They mention that inflation is low despite an "ultraexpansionary" monetary policy because of globalisation and weak labor unions (we will have a look into this in more details in the coming articles).

So is the next Great Inflation just around the corner? This is possible (usually, monetary policy strategies are abandoned only when they stop working well), but unlikely. In my view, Inflation Targeting has been incredibly successful to bring inflation down to a low and stable level. If the Swiss National Bank adheres to this general concept, it would come as a surprise if inflation would spiral out of control in the near future.

Comments

Post a Comment