Is Switzerland in a deflationary trap? Information from the bond market

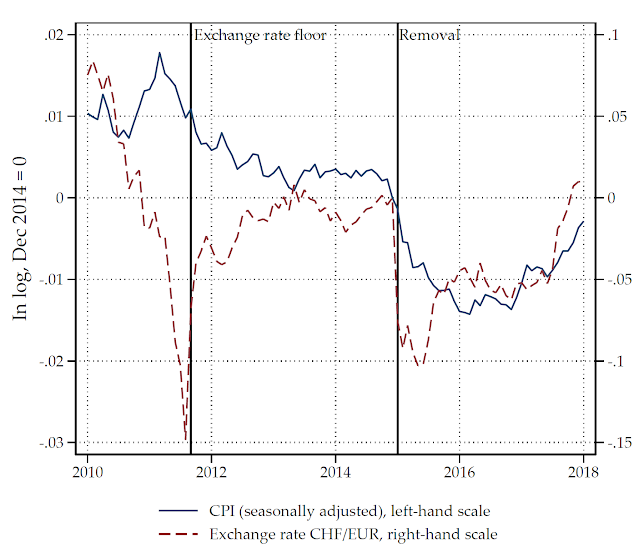

Swiss inflation is back in positive territory. Is it therefore time to raise interest rates? To answer this question it is important not only to look at current but also at expected inflation. If inflation is expected to be low in the years to come it may be premature to raise interest rates.

Economists surveyed by the KOF conensus forecast are optimistic that the SNB succeeds in keeping inflation in line with its mandate: they expect an inflation rate of 0.7% in the short-term and an inflation rate of 1.2% in five years.

Do financial markets agree with this assessment? Unfortunately, we do not have a direct measure of market-based inflation expectations for Switzerland. For the US, however, such a measure can be derived from the yields of inflation-indexed and normal government bonds. Various researchers have recently shown how exploit economic theory and the information available for the US to derive inflation expectations for other countries (see Krugman, Gerlach-Kristen et al., 2017, and Kamada and Nakajima, 2013).

Below I discuss my own estimates for Switzerland and Japan (If you are not interested in the methodology, skip this paragraph!). There are various approaches and I will give the basic intuition of the simplest one that I use. Suppose an investor has to decide to invest its money in a US or Swiss 10-year government bond. If the interest rate on the US bond is 2pp higher than the interest rate on the Swiss bond, this implies that financial markets expect the Swiss franc to appreciate at an annual rate of 2% over the next 10 years. If the Swiss franc would appreciate less, this would imply that investors could make a profit by selling the Swiss bond and buy the US bond. Therefore, we can derive the expected rate of appreciation of the Swiss franc vis-à-vis the US dollar from the difference between Swiss and US government bond yields. In addition, the expected rate of appreciation should be approximately equal to the difference between expected Swiss and US inflation. The reason is that, in the long-run, the real exchange rate should be stable. This is a concept called relative purchasing power parity. Both concepts have their empirical challenges. However, if we are willing to accept these notions, we can calculate Swiss 10-year inflation expecations by adding US market-based inflation expectations to the expected rate of appreciation derived from the relative bond yields (here is the R-code so that you can check what I did and tell me if there's a mistake! Update: download this Excel-file for an extension using a survey of professional forecasters to measure US inflation expectations).

Long story short, here are the results for Japan and Switzerland compared with 10-year inflation expectations for the US. The lines give the expected annualized percent change in the price level over the next 10-years. The results from 2003 to 2008 make a lot of sense. US expectations are close to 2.5%, which is close to the 2% target set (implicitly at the time) by the Fed (the minor difference stems from the fact that the inflation indexed bonds use a different price index than the Fed). Swiss inflation expectations are within the 0-2% range defined as price stability by the SNB. However, the expectations are more volatile. This could be in line with the idea that the target range anchors expecations less strongly than a point target. In addition, inflation expectations in Japan are lower, which is in line with the long deflationary episode Japan has experienced. During the financial crisis, we observe a sharp plunge in US inflation expecations transmitting to inflation expectations in Switzerland and Japan. Moreover, we see the temporary increase in Japan's inflation expectations that researchers associated with the program by Shinzo Abe.

For Switzerland, the most interesting part is the development since 2013. Inflation expectations started to fall towards zero and became negative already before the SNB removed the exchange rate floor. Note that this puts a different interpretation on the removal of the floor. Because of falling inflation expectations, markets expected that the Swiss franc has to appreciate in the future. Basic economic theory suggests that this leads to an immediate Swiss franc appreciation, and therefore, the SNB had to intervene heavily to defend the floor. Recently, inflation expectations are at the same level as for Japan. Taken at face value, this is disconcerting. Rather than thinking about raising interest rates, we should ask ourselves whether the Swiss economy is in a deflationary trap similar as Japan.

This analysis comes with several caveats, however. The economic conditions used to derive these expectations may be wrong. Moreover, if US government bonds contain a higher risk premium than Swiss government bonds we would underestimate Swiss inflation expectations. Such a risk premium may even change over time. Finally, we should take into account that economists expect higher inflation than my estimates suggest.

Despite those caveats, the analysis provides an additional piece of information to judge whether interest rates should be raised or not. It is probably too early.

PS: Of course, using my simple approach the expected inflation differential over the next 10 years is roughly equal to the interest rate differential of 10-year governemnt bond yields between Switzerland and the US. So the decline could indicate a lower relative risk premium of Swiss government bonds relative to US government bonds. However, I don't see any particular reason why the risk premium should have declined over this time period.

Economists surveyed by the KOF conensus forecast are optimistic that the SNB succeeds in keeping inflation in line with its mandate: they expect an inflation rate of 0.7% in the short-term and an inflation rate of 1.2% in five years.

Do financial markets agree with this assessment? Unfortunately, we do not have a direct measure of market-based inflation expectations for Switzerland. For the US, however, such a measure can be derived from the yields of inflation-indexed and normal government bonds. Various researchers have recently shown how exploit economic theory and the information available for the US to derive inflation expectations for other countries (see Krugman, Gerlach-Kristen et al., 2017, and Kamada and Nakajima, 2013).

Below I discuss my own estimates for Switzerland and Japan (If you are not interested in the methodology, skip this paragraph!). There are various approaches and I will give the basic intuition of the simplest one that I use. Suppose an investor has to decide to invest its money in a US or Swiss 10-year government bond. If the interest rate on the US bond is 2pp higher than the interest rate on the Swiss bond, this implies that financial markets expect the Swiss franc to appreciate at an annual rate of 2% over the next 10 years. If the Swiss franc would appreciate less, this would imply that investors could make a profit by selling the Swiss bond and buy the US bond. Therefore, we can derive the expected rate of appreciation of the Swiss franc vis-à-vis the US dollar from the difference between Swiss and US government bond yields. In addition, the expected rate of appreciation should be approximately equal to the difference between expected Swiss and US inflation. The reason is that, in the long-run, the real exchange rate should be stable. This is a concept called relative purchasing power parity. Both concepts have their empirical challenges. However, if we are willing to accept these notions, we can calculate Swiss 10-year inflation expecations by adding US market-based inflation expectations to the expected rate of appreciation derived from the relative bond yields (here is the R-code so that you can check what I did and tell me if there's a mistake! Update: download this Excel-file for an extension using a survey of professional forecasters to measure US inflation expectations).

Long story short, here are the results for Japan and Switzerland compared with 10-year inflation expectations for the US. The lines give the expected annualized percent change in the price level over the next 10-years. The results from 2003 to 2008 make a lot of sense. US expectations are close to 2.5%, which is close to the 2% target set (implicitly at the time) by the Fed (the minor difference stems from the fact that the inflation indexed bonds use a different price index than the Fed). Swiss inflation expectations are within the 0-2% range defined as price stability by the SNB. However, the expectations are more volatile. This could be in line with the idea that the target range anchors expecations less strongly than a point target. In addition, inflation expectations in Japan are lower, which is in line with the long deflationary episode Japan has experienced. During the financial crisis, we observe a sharp plunge in US inflation expecations transmitting to inflation expectations in Switzerland and Japan. Moreover, we see the temporary increase in Japan's inflation expectations that researchers associated with the program by Shinzo Abe.

This analysis comes with several caveats, however. The economic conditions used to derive these expectations may be wrong. Moreover, if US government bonds contain a higher risk premium than Swiss government bonds we would underestimate Swiss inflation expectations. Such a risk premium may even change over time. Finally, we should take into account that economists expect higher inflation than my estimates suggest.

Despite those caveats, the analysis provides an additional piece of information to judge whether interest rates should be raised or not. It is probably too early.

PS: Of course, using my simple approach the expected inflation differential over the next 10 years is roughly equal to the interest rate differential of 10-year governemnt bond yields between Switzerland and the US. So the decline could indicate a lower relative risk premium of Swiss government bonds relative to US government bonds. However, I don't see any particular reason why the risk premium should have declined over this time period.

Comments

Post a Comment